Like many great artists, Currado Malaspina’s best work comes from a place of profound agony. Beneath the fat-headed grandiloquence is a vulnerable romantic cautiously frisking a cruel world in search of hope. While his public persona might be that of a callous, flashy libertine, his true nature is tender, loving and kind.

Like many great artists, Currado Malaspina’s best work comes from a place of profound agony. Beneath the fat-headed grandiloquence is a vulnerable romantic cautiously frisking a cruel world in search of hope. While his public persona might be that of a callous, flashy libertine, his true nature is tender, loving and kind.

I should know because I spent four unforgettable years living and loving this legendary French artist.

One of the rich, corrective dividends of being an ex is that when one carefully tills the furrows of past discord, a true, intimate friendship can develop and grow.

Such is the case with Currado and me. It is my privilege to be taken into Malaspina’s confidence and though I find myself giving much more than I get there is something quite special in having an intimate perspective into the creative genius of one of today’s greatest artists.

Such is the case with Currado and me. It is my privilege to be taken into Malaspina’s confidence and though I find myself giving much more than I get there is something quite special in having an intimate perspective into the creative genius of one of today’s greatest artists.

As is well documented, Currado Malaspina has (so far) been married four times. Each marriage is accompanied by scandal, prurient speculation, salacious innuendo and idle fodder suggesting all manner of copulatory madness outside the sacred sanctuary of wedlock. The truth, as is often the case, is much simpler.

When Currado decides to love he loves hard and any thought of straying from the orchard is happily obliterated. Take it from me – When it comes to fidelity, Malaspina is a Saint Bernard. Women sense this about him and women being women he therefore gets treated like a dust cloth.

Wife number one gave birth to a beautiful daughter – Sabine Héloïse – and within six months ran off with her yoga teacher to Goa to study Ashtanga breathing techniques from an Israeli guru named Alon.

Wife two, a very talented pastry chef and not-too-talented actress tried to lure him away from his studio with any number of hair-brained, get-rich schemes. Currado has about as much business acumen as a toddler selling lemonade and the two of them got so buried in debt that he was forced to exhibit some of his most unmemorable works. Fortunately the name Malaspina carries enough caché that armies of credulous collectors came barking with euros.

#2 eventually sued for divorce and was awarded more than half of his existing oeuvre.

With wife three came with the promise of blissful tranquility and mutual adoration until she got sucked into a Belgian messianic sewing circle.. The way Currado tells it, she turned forty and decided overnight that the most important thing in life was “personal rapture.”

It was there where she learned how to use the cumbersome neologism ‘defoliating opportunity,‘ (opporunité défoliante).

Forgetting for a minute the sinister connection to clearing jungle war zones with toxic herbicides, the idea is essentially to annihilate any self-critical, introspective insights in favor of unambiguous affirmation. It’s a clever form of denial which tends to treat psychic pain with a Bugs Bunny Band Aid. To the philosopher in Currado this sort of linguistic floor-bending was maddening.

He left the infantilized #3 the day she took him to her Renewal Assignment Ceremony where each guest was presented with a brightly colored ball of yarn and was encouraged to “exchange anguish points” with the person seated next to them.

He left the infantilized #3 the day she took him to her Renewal Assignment Ceremony where each guest was presented with a brightly colored ball of yarn and was encouraged to “exchange anguish points” with the person seated next to them.

Wife number four, who some say resembles a younger version of me, is an attorney who works in the French ministère du budget, des comptes publics et de l’administration civile. By all accounts she’s a very competent bureaucrat who performs her duties with diligence and integrity. I think that by marrying Currado she hoped to establish her credibility as a formidable woman of culture, a quality of some value among the Parisian haute bourgeoisie. As one might expect, she’s a rather cold fish and treats Malaspina like a household appliance.

I know he’s dying inside – he as much as told me so when I visited him last summer.

Currado is a good man. He’s a man in very close contact with the world of the senses. He values love above all else and celebrates its possibility with childish optimism.

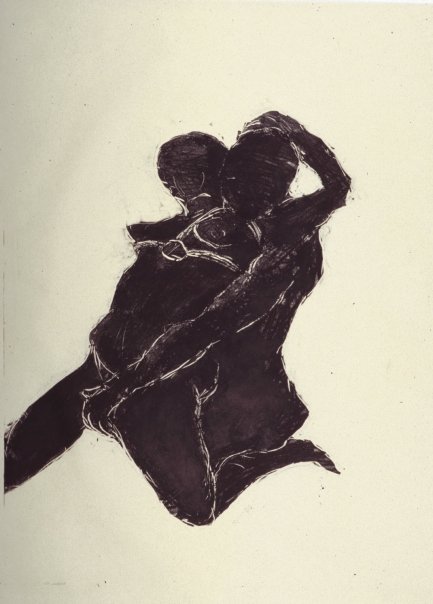

Critics are quick to over-interpret his art, seeing in his lurid images hints of bitterness, vulgarity, misogyny and lust. That was never really the case. Malaspina’s work has always been about humor, poetry and joy. What some see as badly drawn soft pornography he sees as a post-modern exegesis on Ovid’s evolving relationship to the history of painting.

Perhaps he’s doomed. Perhaps he’s one more reckless romantic, crushed on the asphalt of our age of monotonous velocity. He’s a voluptuary on a vélo while an unreflecting, routinized world is obsessed with the predictable seductions of speed.

I’m waiting till his current bride overplays her precious hand. She doesn’t deserve such a rare beacon of decency. I’m waiting, Currado and I’m ready to give us another chance.

Je t’aime, mon amour …